Impact of Supervision and Self-Assessment on Doctor-Patient Communication in Rural Mexico

Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs (Kim, Figueroa, Kols); Fronteras, The Population Council (Martin); Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Programa Solidaridad, or IMSS/S (Silva, Acosta); Universidad Veracruzana (Hurtado); Quality Assurance Project, Center for Human Services (Richardson)

"Supportive supervision and self-assessment changed providers' communication patterns, increasing the amount of facilitative communication, shortening their utterances, and accelerating the exchange of conversations. These alterations suggest that doctors adopted a more client-centred, less authoritarian approach to care along with a more participatory style of communication - changes that researchers have found produce better health outcomes."

This study examines the impact of a combined intervention of supervision and self-assessment on the communication performance of resident doctors at rural clinics in the state of Michoacan, Mexico. Specific objectives are: (1) to determine if supervision and self-assessment help doctors to apply newly learned communication skills on the job and to improve those skills over time; and (2) to identify which activities (including supervision visits, audiotaped consultations, self-assessment, homework logs, and job aids) are effective and acceptable to doctors.

The Mexican Institute of Social Security/Solidarity (IMSS/S) developed the intervention in light of research showing that the quality of communication between doctors and their patients contributes to health outcomes as well as patient satisfaction. Good communication and counseling skills are especially important in rural areas of Mexico, where there are wide cultural differences between indigenous communities and doctors. Furthermore, formative research shows that resident physicians are less skilled in listening to clients, encouraging them to speak, and responding to individual client needs.

This study assessed a cohort of resident doctors who began their assignment at an IMSS/S clinic in Michoacan, Mexico in the summer of 1998. Soon after they arrived, all of the doctors attended a 2-day workshop on interpersonal communication and counseling (IPC/C), followed by a half-day refresher course 5 months later. Baseline data were collected immediately after the refresher course. The doctors were assigned to intervention and control groups depending on which supervision zone their clinics belonged to. During the following 4 months, doctors in the intervention group received visits from supervisors who were specially trained in IPC/C and who evaluated doctors' interactions with clients; some of these doctors also conducted IPC/C self-assessment exercises. Specifically, each doctor was asked to audiotape two consultations a month, with the permission of the patients. The doctors listened to the tapes and assessed their communication performance with the help of a job aid. Some doctors also completed written self-assessment forms focusing on specific communication skills. (Their supervisors received additional training to support this activity.) Doctors in the control group also received regular supervision visits, but their supervisors were not trained in IPC/C and did not review how well they communicated with clients. (They did not receive the job aid, a tape recorder, or any other intervention materials.) At the end of the 4-month intervention period, a second round of data was collected.

The data are analysed in two different ways: a cross-sectional comparison and a panel study. The cross-sectional analysis compares post-intervention measures in the intervention and control groups, and it has the advantage of a larger sample size. The panel study examines changes over time from the baseline to post-intervention rounds in both the intervention and control groups. Audiotaped consultations, which were coded for content using the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS), are the primary source of data for this study.

Outcome measures:

- Doctor facilitative communication, i.e., communication that promotes an interactive relationship between patient and doctor by fostering dialogue, rapport, and patient participation. Four of the intervention's 6 IPC/C content areas were designed to encourage facilitative communication: active listening, being responsive to patients, encouraging patient participation, and expressing positive emotions.

- Information-giving by doctors. One of the intervention's IPC/C content areas encouraged doctors to provide more and better medical and technical information to patients.

- Patient active communication, which includes: asking questions, asking for clarification, expressing an opinion, expressing concerns, and discussing personal and social issues.

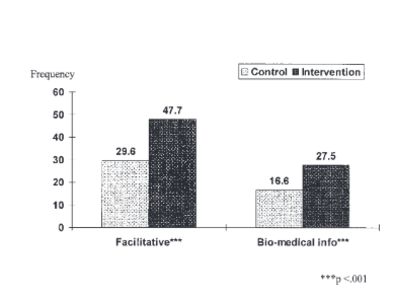

The performance of all doctors improved markedly over the study period, but gains in facilitative communication and information-giving were significantly greater in the intervention than the control group. Doctors in the intervention group outperformed the others during the post-intervention round, with an overall frequency of facilitative communication of 48 compared with 30 for the control group (P < 0.001). Even after controlling for the purpose of the visit, the sex of the doctor, and the length of the session, the intervention showed a significant impact on facilitative communication (ß = 0.28, P < 0.001). Doctors in the intervention group performed significantly better than those in the control group on 3 of the 6 types of facilitative communication: partnership building (12.7 versus 7.3, P < 0.001), acknowledgement (12.3 versus 6.2, P < 0.001), and expressing positive emotions (5.9 versus 2.9, P < 0.001).

The panel study confirms the intervention's impact on facilitative communication. Levels of facilitative communication rose 238% in the intervention group (from 13.6 to 45.9, P < 0.001) and 124% in the control group (from 14.6 to 32.7, P < 0.001). After controlling for other factors in a multiple regression analysis, this rise was significant in the intervention group (ß = 0.23, P < 0.01) but not in the control group (ß = 0.20, not significant). Since the control group also attended IPC/C training, received routine supervision, and learned from their growing experience with patients, it is no wonder that their levels of facilitative communication increased as well.

When the impact of each component on facilitative communication was assessed separately, a significant positive association was found with the number of supervision visits received (ß = 0.25, P < 0.001), the number of sessions audiotaped (ß = 0.20, P < 0.01), the number of self-assessments performed (ß = 0.19, P < 0.01), and the number of times the homework log was used (ß = 0.13, P < 0.05). (It was impossible to assess the impact of the job aid, since all doctors reported using it frequently.) Only the number of supervision visits remained significant, however, when all of the intervention components were entered in the regression (ß = 0.20, P < 0.05).

Following the intervention, doctors in the intervention group provided 63% more biomedical information and counseling than those in the control group (27.5 versus 16.6, P < 0.001), and this difference remained significant even after controlling for other factors (ß = 0.26, P < 0.001). The panel study confirms this finding: Information-giving increased from 7.8 to 25.1 (P < 0.001) in the intervention group, compared with a rise from 7.7 to 16.6 (P < 0.001) in the control group. After controlling for other factors, these increases remained significant both in the intervention (ß = 0.44, P < 0.001) and control groups (ß = 0.42, P < 0.05). However, the rate of change was significantly greater in the intervention than control group (P = 0.0001).

The frequency of patient active communication did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups. The panel study showed that the frequency of patient active communication increased dramatically over the study period in both the intervention (from 2.4 to 12.7, ß = 0.07, P < 0.001) and control groups (from 2.6 to 13.0, ß = 0.13, P < 0.01), with no significant difference in the rate of change between the two groups. This general increase in active communication may be due to providers’ growing experience and the increased length of the sessions, rather than the indirect impact of the intervention.

In focus group discussions, doctors in the intervention group reported that supervisors offered them more and better feedback on communication and counseling issues after the intervention began. Doctors also noted changes in supervisors' IPC: Supervisors began working with the doctors as partners, listening to their ideas, and engaging them in discussion, and were more appreciative of their efforts. Doctors initially found the self-assessment process stressful, especially those who did not receive written self-assessment forms and instructions. With repetition, however, doctors became proficient at self-evaluation and found that the tapes helped them recognise their strengths and weaknesses and provided strong motivation to improve.

Reflecting on this experience with partnership supervision, the researchers suggest that the intervention acknowledged the continuing importance of supervisors' normative function in the creation of an observation checklist to assess doctors' IPC/C performance. However, the emphasis on feedback, 2-way discussion, and the homework log added a formative, educational dimension that helped doctors improve their skills. Training in IPC also helped supervisors perform a restorative function, providing emotional support to, and ensuring the personal well-being of, staff members, which takes on even more importance when young, inexperienced doctors are assigned to live and work in isolated rural clinics.

Research also points to the importance of reflection for professional decision making and adult learning. For doctors, listening to the audiotapes was a powerful experience, and self-criticism was a more compelling motivator than outside criticism. While audiotaping consultations proved to be an effective learning tool, IMMS/S found it difficult to supply tape recorders to scattered rural clinics and maintain them in working order once the intervention was scaled up.

"Because supervision and self-assessment activities and materials were designed to complement and build on each other, it is difficult to single out the effectiveness of any one component of the intervention. Results suggest instead the importance of multiple, reinforcing interventions for promoting self-learning and behavioral change....Further research is needed to test different forms of IPC/C supervision and self-assessment, and to refine the balance between them."

International Journal for Quality in Health Care, Volume 14, Issue 5, 1 October 2002, Pages 359–367, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/14.5.359.

- Log in to post comments